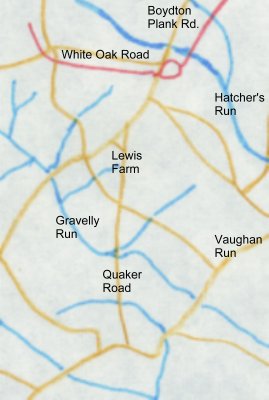

Overview The Battle of Five Forks is the most well-known of the later battles of the siege, and also the most controversial. A complete discussion actually involves four separate fights: Lewis Farm or Quaker Road (March 29), White Oak Road (March 31), Dinwiddie Court House (March 31), and Five Forks (April 1) itself. Some discussion of the terrain and road network is appropriate at this point. (For a map covering this series of actions, click here.) The Federal lines were close to Petersburg only along the eastern side of the city. As the lines curved to the west they also tended to angle away from town. At Fort Fisher, a point about 3 miles southwest of the city, the Federal main line actually doubled back and formed a huge enclosed loop. This position was on the site of Peebles Farm, and had been seized during the Fort Harrison-Peebles Farm operation of the previous fall. At this point, the Confederate lines also began to angle southwestward away from the city, covering the Boydton Plank Road. About seven miles southwest of town, the Rebel lines reached Hatcher's Run, which flows from northwest to southeast and was a substantial military barrier. The main Rebel lines stopped at Hatcher's Run, with several strong redoubts to cover the flank, but a further set of trenches had been built to the west, along White Oak Road. This set of works ran east-west and covered the section of White Oak Road from the Boydton Plank Road west to the Claiborne Road. These were the only two roads by which the Yankees could directly approach the Confederate flank. Grant's plan for finally turning Lee out of Petersburg --- or trapping his army within its lines --- was a simple and well-conceived continuation of his relentless leftward lunges of the past year. Phil Sheridan would lead a cavalry strike force of three divisions out beyond the Rebel flank, to Five Forks, a major road intersection about ten miles west-southwest of Petersburg, and about five miles west of where Lee's lines ended. From this position Sheridan could threaten the rail lines that served Petersburg or the Rebel position itself. Federal infantry would press up to the Rebel lines along White Oak Road and even try to connect with Sheridan. If the way was open to turn Lee's flank then Sheridan was to do so, otherwise he would cut loose with his horsemen and make a large-scale raid on the railroads. In addition to the Army of the Potomac troops, Grant had Maj. Gen. E.O.C. Ord bring two divisions of John Gibbon's XXIV Corps of the Army of the James (reinforced by one division of XXV Corps, and accompanied by a cavalry division under Ranald MacKenzie) across the Appomattox river, in secret, to be used as events developed. Together with Warren's V Corps and Humphreys's II Corps on the left end of the Federal trench lines, this gave Grant three infantry corps (nine divisions) and three cavalry divisions, totalling 54,500 infantry and 13,000 cavalry. Such a force under vigorous tactical direction would be unstoppable. Still, the Rebels tried, and tried hard. Lee's options for dealing with Grant's move were limited. As of March 27, his army was deployed as follows:

In addition to these troops, Lee had available the First Corps division commanded by Gettysburg "hero" George Pickett, posted in Chesterfield County as a quasi-reserve, and two divisions of cavalry guarding the Weldon Railroad at Stony Creek Station, some 25 miles south of Petersburg. The Confederate lines were thinnly held, one estimate being that there were fewer than 1200 men per mile of defended line. Anticipating Sheridan's advance, Lee ordered Pickett and all three of his cavalry divisions to concentrate at the crossroad known as Five Forks. Together with Anderson's force along White Oak Road, this would give Lee had a total of only eight infantry brigades and seven cavalry brigades to oppose any Federal force west of Hatcher's Run. Still, Marse Robert had no intention of changing his combative ways. Fitz Lee --- put in charge of all the cavalry --- and Pickett --- given overall command of the Rebel force --- were ordered to attack and defeat Sheridan's cavalry. The Federal columns began moving on March 29th, just a few days after Lee's failure at Fort Stedman, with Sheridan taking a wide circuit to the south, west and then north, aiming for Dinwiddie Court House, a key road junction. Meanwhile, V Corps took a slightly shorter route to approach the White Oak Road position from the south, and II Corps swung out to fill the gap between V Corps and Ord's men on the left of the Federal trench lines. |

|

|||||||||||

The Battle of Lewis Farm (March 29, 1865) Maj. Gen. Gouvernor K. Warren's V Corps had the task of maintaining contact between the Federal main lines and Sheridan's cavalry, and of supporting Sheridan's flanking effort. In order to do so, Warren's troops had first to move southwest behind the Federal lines, cross Rowanty Creek, then turn northwards along the Quaker Road, cross Gravelly Run, and strike for the enemy lines along the White Oak Road. While moving northward along the Quaker Road on March 29th, Warren's lead division, under Griffin, began to encounter serious opposition at Gravelly Run, where the Rebels had destroyed the bridge and then constructed light earthworks on the north bank, disputing the Federal advance. Griffin's lead brigade commander, Brig. Gen. Joshua Lawrence Chamberlain (seeing his first serious action since his near fatal wounding the previous June), deployed part of one regiment to engage the Rebels in a firefight while he personally led another force across the flooded run to take the Rebel position in flank. This caused the Confederate position to collapse and the graycoats retreated up the Quaker Road to their main position near the Lewis farm, about one mile short of the intersection of the Quaker Road with the Boydton Plank Road. The Rebels consisted of four brigades under the direct command of Maj. Gen. Bushrod Johnson, charged with keeping the Federals from reaching the long-sought and vital artery of the Boydton Plank Road. Supported only by Gregory's brigade, Chamberlain continued to press forward, driving all the way to the Plank Road but being forced to fall back when hit with a fierce Confederate counterattack. The Rebels, however, had their hands full just with Chamberlain's force, and could do nothing to prevent Griffin and Warren from extending the Federal line to the left. Bushrod Johnson had no answer to this move, and so was compelled to fall back, first to the Boydton Plank Road, then, after a further Federal advance at dusk, all the back to the White Oak Road position. Because of the efforts of Griffin and Chamberlain, Warren's Federals had obtained a position along a ridge overlooking the White Oak Road, threatening the Rebel entrenchments and astride the vital Boydton Plank Road. Both arteries were vital to Lee's communications, as the White Oak Road was the only direct route between Petersburg and Pickett's force opposing Sheridan, and the Boydton Plank Road was a necessary part of Lee's fragile communications with the rest of the Confederacy. If the White Oak Road could be taken and held, Pickett would be essentially cut off from the Rebel main body. Humphreys had brought II Corps up on Warren's right, forming a junction with Ord's men in the main Federal trenches. (So far the Confederates were unaware that Ord had left the Richmond lines.) If Warren had been stopped short, it might have delayed and confounded the Yankee operation enough to allow Pickett and Fitz Lee the time to defeat Sheridan. In addition, the Federal position was one from which it might be possible to flank Lee's lines and complete the investment of Petersburg. |

|

|||||||||||

The Battle of Dinwiddie Court House (March 31, 1865) Sheridan reached Dinwiddie Court House late on the 29th. The events of the day had been so favorable to the Federal operation that Grant told Sheridan that the railroad raid option was no longer in play; the Federal cavalry, with V Corps as support, would swing around Lee's line and finish the job of enclosing Petersburg. Sheridan was to strike north for the vital road junction known as Five Forks, from which position he could easily reach Sutherland Station on the Southside Railroad. Accordingly Sheridan sent one division (Devin) to occupy Five Forks that night, but upon approaching the intersection it was discovered that the Rebels were present and a position was taken up astride the road leading south from Five Forks to Dinwiddie. Although the Confederates did not know the details of the Federal operation, they knew that possession of Five Forks would give Sheridan a clear road in any of three important directions: east, to the rear of Lee's trench lines along the Boydton Plank Road; north, to the vital Southside Railroad; and, west, to the equally vital Richmond and Danville Railroad. Lee simply could not allow Sheridan to reach Five Forks; the Union cavalry had to be defeated. A heavy rain on March 30th turned the roads into mud and brought a brief halt to the Union advance. On the 31st, Sheridan was to take Five Forks and Warren was to envelop the White Oak Road line on its right, to prevent Lee from using that road to send more troops to oppose Sheridan. However, Pickett and Fitz Lee launched their attack on Sheridan first. The Federal troopers were widely dispersed and had no infantry support, and were forced to give ground, albeit grudgingly. The first attacks came from the west, where Pickett's infantry, reinforced by some of the same troops that had opposed Warren on the 29th, forced a crossing of a stream known as "Chamberlain's Bed" and drove back the single Yankee horse brigade defending the crossing. A similar effort further south was repulsed, but Pickett's success forced the blue troopers to fall back on Dinwiddie Court House. The attack on Five Forks would have to be postponed to deal with the enemy attack. In fact, the force that was supposed to take the vital road junction had to be pulled back in order to delay the advancing Rebel infantry. By early evening, Pickett had swung his force to the right and pushed south, almost to Dinwiddie Court House itself. Although this part of the day had been a success for Confederate arms, it needs to be said that Sheridan had fought Pickett for the most part with only four cavalry brigades, parts of two divisions under Thomas Devin and George Crook. Custer's division, which had been in the rear guarding the Cavalry Corps wagon train, rendered support at the end of the day. Sheridan's immediate comments on the battle were interesting and contrasting. At one point he told Grant that Pickett's force was "too strong for us. I will hold on to Dinwiddie Court-House until I am compelled to leave." Yet in another (later) message he made the cogent observation that the enemy force "is in more danger than I am in --- if I am cut off from the Army of the Potomac, it is cut off from Lee's army, and not a man in it should ever be allowed to get back to Lee. We at last have the enemy's infantry out of its fortifications, and this is our chance to kill it." Whatever the extent of Sheridan's worries for his own position, he clearly was thinking more in terms of doing damage to the enemy than simply saving his own force. But he needed infantry support to accomplish that goal, and that would have to await the next day. The Battle of Dinwiddie Court House gets little attention in most studies of the siege of Petersburg, no doubt because of the momentous events of the next day. But to ignore this fight is to ignore much of the motivation and context for what happened at Five Forks. Pickett had indeed won something of a victory by pushing Sheridan back, although it is not clear how hard the Federals tried to maintain their position. However, Pickett's advance, while threatening to cut Sheridan off from the Federal main body, also threatened to cut Pickett off from Lee. It was the presence of Pickett and Warren in each other's rear that precipitated much of the controversy about the Battle of Five Forks. |

|

|||||||||||

The Battle of White Oak Road (March 31, 1865) Based on the results of the fighting of March 29th, Grant modified and firmed up the objectives of the operation. Phil Sheridan's cavalry force on the left flank would advance through Five Forks and Sutherland Station to turn Lee's right flank and complete the investment of Petersburg. If Lee was not able to stop Sheridan, his army would be trapped and forced to surrender. To support Sheridan's effort, an infantry corps would be needed; Sheridan asked for the VI Corps, which had served with him in the Shenandoah Valley, but it was too far away to reach him in time. The nearest infantry was V Corps, under the problematical Gouvernor K. Warren. Accordingly, Warren was assigned to Sheridan and ordered to turn the White Oak Road line on its right (the Federal left). Humphreys with the II Corps would be on Warren's right. The movement was supposed to occur on March 30th, but heavy rains forced a day's delay. After waiting out the rains of March 30th, Warren continued his advance on the morning of the 31st, probing cautiously forward towards the White Oak Road position to turn it on its right. As with almost all of his advances during the siege, it was poorly handled. The corps was deployed in a column of divisions, with Ayres leading, followed by Crawford; Griffin, who had borne the brunt of the fighting on the 29th, was held in reserve. Despite Grant's comment of the night before, that "Warren should get himself strong tonight," neither advancing division had any flank supports, and the force was advancing on a narrow front. In other words, V Corps was a tempting target for just the kind of counterpunch that Robert E. Lee had made his reputation with --- and Lee himself was on the scene to administer the blow. The Rebel commander could no more allow Warren to turn Anderson's flank than he could allow Sheridan to reach Five Forks. The blow was delivered shortly after 10:30 in the morning, by a motley collection of four Confederate brigades from three different corps (McGowan's Brigade, of Heth's Division in Hill's Third Corps, Hunton's Brigade, in Pickett's Division of Longstreet's First Corps, and Moody's and Wise's Brigades of Bushrod Johnson's Division from Anderson's Fourth Corps), which struck Ayres in front and flank and crumpled his entire division. The fleeing Federals disordered Crawford behind them, who was therefore unable to withstand the continuing attack. In a sad scene indicative of Warren's leadership of the entire last year of the war (one of Meade's staff said of Warren that he was incapable of spreading himself over as much as three divisions), a brief combat of 30 minutes had allowed a force of three Confederate brigades to rout two-thirds of V Corps. (Wise's brigade participated in the advance but was not seriously engaged.) The Federals had advanced almost to the White Oak Road itself when the counterattack was launched, and they were driven back almost to the low ridge where Griffin's division and the Corps artillery had been posted in reserve. Lee was able to quickly ascertain that his force was not strong enough to follow up the initial success, and so the victorious Rebels were instructed to halt their advance at a small line of entrenchments that Warren had built the previous day. Reversing and strengthening this line, and connecting it to the rest of the Confederate trenches, might be enough to protect the White Oak Road and foil the Federal advance. The battle thus settled down into a lull. The Rebels were occupied with improving and consolidating their gains, while the Yankees were rallying their routed brigades. Meanwhile, requests for help had gone to II Corps on Warren's right, and Humphreys accordingly prepared to attack with his left division, under Miles. By about 2:30 Warren was ready to try again. Griffin's division led the way, with Chamberlain's brigade once again in the van of the attack. Crawford's reformed troops were on Griffin's right and Miles was on Crawford's right. Ayres supported Griffin on the left. The initial advance was against only skirmisher opposition, until the new line of Rebel works was reached. Although Chamberlain's line wavered slightly under some telling artillery fire, the Rebels were not able to disrupt the advance and were not able to hold their own position, and retired to their main line of works. The Federals were not done, however. Chamberlain continued forward and to the left, crossing the White Oak Road in strength (this was about 3:40 p.m.) beyond the Rebel works and then taking up a position in front of the main Rebel line. One Confederate regiment, the 56th Virginia, was trapped outside the works and captured almost entire. Warren was able to see enough of the enemy works to convince himself that an attack on the main White Oak Road line was not a practical idea, but he had broken the connection between Pickett and Lee.

|

|

|||||||||||

The Battle of Five Forks (April 1, 1865) To understand Five Forks one must understand the confused positions of the several detachments confronting one another southwest of Petersburg, starting on the evening of March 31st. Sheridan's cavalry was holding on at Dinwiddie Court House, but just barely so, along a line that ran east-west and faced north. Pickett, with around 10,000 or so infantry and cavalry, was facing him. However, Warren's V Corps was about three miles north and east, in Pickett's rear. While Pickett's success of the day had indeed threatened to cut Sheridan off from the Union main body, it had likewise (coupled with Warren's success along the White Oak Road) threatened to cut Pickett off from Lee. The controversies of April 1st all have their roots in the attempts by the Yankees to take maximum advantage of the opportunities presented by these postions, and at the same time protect themselves from the opportunities presented to the enemy. Muddying the waters to no small extent was the fact that no commander on either side was entirely aware of the precise situation in time to take complete advantage of it. Both Grant and Lee were sufficiently far from the scene that communication delays often resulted in orders being based on out-of-date information. Grant and Sheridan both appear to have understood the basic situation, that Warren was well-placed to trap Pickett's force and force its destruction. Unfortunately, the precise means by which this would be accomplished was unclear. On the evening and night of March 31-April 1, Warren received a baffling series of orders about sending help to Sheridan, some very specific, some vaguely general, all of them acting at cross-purposes, and some arriving out of sequence. Some troops were sent directly from Warren's advanced position along the White Oak Road to press up against Pickett's left rear, while others were ordered to withdraw to the Boydton Plank Road for a direct march to Dinwiddie Court House and Sheridan's lines. In a crucial but often overlooked message, Grant told Sheridan that he could expect V Corps to arrive at around midnight. While this was a reasonable estimate of the marching time, it did not take into account the time required to reassemble the Federal divisions and disengage from the enemy, nor was this estimate modified in the light of the delays in eventually deciding what Warren should do and how he should do it, nor was Grant aware that a bridge over Gravelly Run would have to be rebuilt. As Federal divisions marched to-and-fro that night, some contact was made with elements of Pickett's command. This alerted the Confederate commander to the unpleasant fact that Yankees were in his rear and caused him to order a night-time withdrawal. Pickett's intent was to pull back as far north as Hatcher's Run, where it is crossed by the Ford Road leading from Five Forks, but a message from Lee ordering him to "hold Five Forks at all costs" and expressing "regret" that Pickett had been forced to fall back caused Pickett to take up the fateful position at Five Forks along the White Oak Road. His left did not connect with the rest of the Confederate army and so the entrenchments were refused northwards about one mile east of Five Forks. The gap between Pickett's left and Anderson's right (along White Oak Road) was supposed to be covered by an understrength North Carolina cavalry brigade under William P. Roberts, the youngest general in the Confederate army. Pickett compounded his weak position by poorly positioning the few guns at his disposal; after the war one gunner commented that Pickett "knew more about brands of whiskey than he did about the uses of artillery." For his part, Sheridan spent an anxious and infuriating night. The supporting infantry that he needed to strike a strong blow at the enemy did not arrive until the morning of April 1st. To compound the problem, Warren had decided that withdrawing from close contact with the Confederates along White Oak Road required the corps commander's personal attention, and so he he was at the rear of the column of march, decidedly not where Sheridan thought he should be. Warren exacerbated this bad impression when he took over three hours after he did arrive to report to Sheridan for orders. It took most of the morning of April 1st for Sheridan's cavalry to advance and develop Pickett's lines. Meanwhile, V Corps assembled near the J. Boisseau farm. At about 1 p.m., the infantry was ordered forward to the vicinity of the Gravelly Run Methodist Episcopal Church, where they would form for battle. At about this time Sheridan and Warren held a brief conference, at which the plan of battle was decided upon. While the cavalry demonstrated against the Confederate front, V Corps would march forward on a diagonal course to the northwest and strike the "knuckle" where the Rebel line was refused, thus caving in the enemy defenses. Sheridan was greatly upset at what he thought were the continuing delays in Warren getting his troops formed. There were two tragic problems with this plan. First, the knuckle was not where Sheridan and Warren thought it was, it being some distance to the west. Thus V Corps, if undisturbed, would march forward into empty space behind Pickett's lines. Secondly, Sheridan had received a note from Grant authorizing him to replace Warren if he (Sheridan) felt that V Corps would perform better under one of the division commanders. This order was sent primarily as a result of a courier's report from late that morning, to the effect that V Corps was hung up crossing Gravelly Run. While there had been a delay at that crossing it had been brief and did not contribute substantially to subsequent events, the courier's report did not reach Grant's headquarters until much later, and it created the impression that V Corps was still delayed in its march to support Sheridan. Thus Grant thought that Warren had dallied too much in crossing a small creek. The Federal attack finally stepped off at 4:15 p.m. on April 1st. While Sheridan's troopers skirmished with Pickett's main line, Warren's infantry marched off into the gap beyond Pickett's left. Warren had deployed his men with Crawford on the right and Ayres on the left of the front line, and Griffin behind Crawford in a second line. The first contact that V Corps had with Rebel troops was infantry and artillery fire directed at the left flank of Ayres, coming as the blue troops crossed the White Oak Road. Ayres was a competant division commander, and he quickly figured out the problem and wheeled his division to the left to attack the Confederate line. However, since Crawford was still moving forward, this opened a large gap in Warren's line, which was promptly filled by Griffin's First Divison from the second line. From Sheridan's perspective, however, things were going badly wrong, since his supporting infantry was not engaging the enemy. To compound the error, Warren --- who understood at least part of the problem, and had ridden off to correct Crawford's direction of march --- could not be found to rectify the situation. It was at about 5:00 p.m. that the weight of the Federal infantry began to quickly overwhelm Pickett's left flank. Ayres's attack overlapped the two thin brigades (Wallace's South Carolininas and Ransom's North Carolinians) holding the refused line and nearby front. While this success did disorganize Ayres's troops somewhat, Griffin's division was immediately at hand to follow up the initial success. Unable to hold the onslaught, Confederate resistence collapsed. Pickett himself, and several of his senior subordinates --- including Fitz Lee --- were blissfully unaware that a battle had even opened, having repaired northward along the Ford Road to Hatcher's Run for the infamous shad bake. The Confederates tried to make a stand at several points along their line as Ayres and Griffin rolled up the flank, but it was to no avail, and most of the Confederate force was pushed westwards. Warren finally got Crawford's division re-oriented, and it was these troops that swung in far behind Pickett's line to take the last Rebel resistance in the rear, and cut off the northward retreat of many of the Confederates. Ironically, Crawford's error in continuing northward had ultimately made the Federal victory greater than it probably would have been, by scooping up large numbers of prisoners and forcing the remnants of Pickett's force to the west, away from the rest of Lee's army. Sheridan did not see it that way. All he knew was that V Corps had not attacked when he wanted them to, where he wanted them to, and when he had tried to find the V Corps commander to prod him into action, Warren was not to be found. It was this combination of circumstances that led Sheridan to exercise the authority given to him by Grant. Warren was relieved of his command and Griffin took over V Corps. The length of the combat is difficult to determine. One source places Ayres's attack on the Confederate flank as occuring at 5:00, and other sources note that Lee ordered Anderson to send reinforcements to succor Pickett at 5:45, making the entire battle something less than an hour in duration. Losses at Five Forks are estimated at 830 Federals and around 3,000 Confederate, mostly captured. Among the Confederate dead was William Johnston Pegram, the youthful but veteran artillerist whose older brother had been killed two months previously, while commanding an infantry division under Gordon. Horace Porter carried the news of Sheridan's success to Grant's headquarters, arriving at around 9 p.m. After listening to Porter's report, Grant walked into his tent, wrote out some orders and came back out, handing the paper copies to an orderly to be taken to the field telegraph. "I have ordered an immediate assault along the lines," he announced.

V Corps attacks at Five Forks |

|

|||||||||||

|

Return to Siege main page. Return to list of accounts. Go to previous page. Go to next page. |