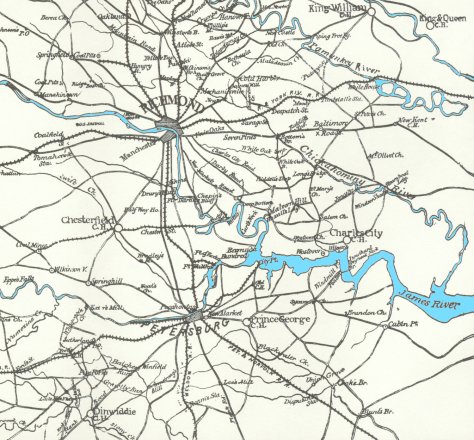

| The city

of Petersburg is situated on the south side of the

Appomattox River, about 23 miles south of Richmond. The

military importance of this small town -- in 1860, it had

a population of about 18,000 -- was due almost entirely

to railroads: Of the three railroads that led to Richmond

from outside of Virginia, two went through Petersburg and

the remaining one passed nearby. Federal occupation of

Petersburg would virtually isolate Richmond and force the

evacuation of the Confederate capital. The vulnerability of Richmond to an attack from the south had been recognized as early as July of 1862. Following his defeat in the Seven Days battles, Gen. George McClellan had wanted to transfer the Army of the Potomac to the south side of the James River to operate against Petersburg, but by some accounts he decided against the idea in favor of renewing his direct campaign against Richmond. In any event, the removal of the bulk of his army to Northern Virginia ended the immediate threat to Petersburg. In 1864, the notion of a water-borne operation against Richmond was revived by Lt. Gen. U. S. Grant, who made it an integral part of his campaign plan in Virginia. While the Army of the Potomac proceeded overland from its winter camps in Culpeper, to engage and pressure the Army of Northern Virginia, the newly-formed Army of the James would advance by transport up the James River and land at Bermuda Hundred, a defensible neck of land between the Appomattox River to the south and the James River to the north. Butler would then advance northward against Richmond, destroying the single rail line that connected the two cities. Unfortunately, after landing on May 4th, 1864, Butler did not move with sufficient celerity to prevent Confederate reinforcements from being gathered from North Carolina, and mid-May found his army solidly corked up in a defensive posture at Bermuda Hundred, having been defeated by Gen. P.G.T. Beauregard at the Battle of Drewry's Bluff on May 16. (For a more complete discussion of this campaign, click here.) Meanwhile, the Army of the Potomac advanced steadily southwards against Lee, sometimes engaging in great and bloody battles (the Wilderness, Spotsylvania) and sometimes not (North Anna, Totopotomoy Creek). By early June Lee and Grant were face to face a mere four miles east of Richmond, just north of the swampy Chickahominy River. On June 3rd, Grant attacked Lee at Cold Harbor but was handily repulsed, with heavy losses. The assault at Cold Harbor marked a temporary pause in the marching and fighting that had been the seemingly endless lot of the two armies since early May. Lee detached Jubal Early and Second Corps to prevent a Federal column from taking Lynchburg, and Grant sent Phil Sheridan with two cavalry divisions to raid the Virginia Central Railroad, the line that connected Richmond to the Shenandoah Valley. If the fighting had reached a lull, the thinking and planning had not. Grant's operations throughout the war are marked by a degree of flexibility unmatched by any other officer on either side. He had conceived the plan of campaign in Virginia with the hope that it would be swift and bloodless, with Lee forced to withdraw under great pressure due to the loss of his communication lines to the rest of the South. The failure of the James River campaign ruled otherwise. However, he had planned ahead for the possibility of taking the Army of the Potomac to the south side of James River, by having a siege train and large quantity of pontoon bridging equipment assembled at Fort Monroe. On June 12 he put his troops in motion on the most crucial maneuver of the campaign. (Meanwhile, Butler had launched a raid against Petersburg with the objective of destroying the railroad bridge over the Appomattox River. The raid failed, in what is known as "the battle of old men and young boys.") Stealthily withdrawing from Lee's presence and moving swiftly to the north bank of the James just east of Wilcox's Landing, Federal troops began crossing on one of the longest pontoon bridges yet built. Some troops crossed by steamer, and one entire corps (the XVIII, from Butler's army, which had reinforced the Army of the Potomac at Cold Harbor) took steamers from West Point Landing. The objective of the entire move was Petersburg and its railroads. The key to the success would be the Federal ability to keep Lee in the dark as to his intentions. Lee could not afford to gamble with his back against his own capital. The Federal V Corps, covered by a single division of cavalry, demonstrated southeast of Richmond on June 13-14, making the Confederates think that this was the Federal main body. Meanwhile, the Yankees had actually crossed the James and were closing in on Petersburg. Leading the march was Maj. Gen. W. F. "Baldy" Smith with the XVIII Corps. Defending at Petersburg were about 2,800 men under Gen. P.G.T. Beauregard.

|

|

|||||

|

Return

to Siege main page. Return to list of accounts. Go to next page. |